On 12 June 2004, a Richard Spruce Day was held, at which a Richard Spruce trail was unveiled, linking the villages and sites associated with Spruce, and a trail leaflet was published. The text and pictures from the leaflet follow.

On this page:

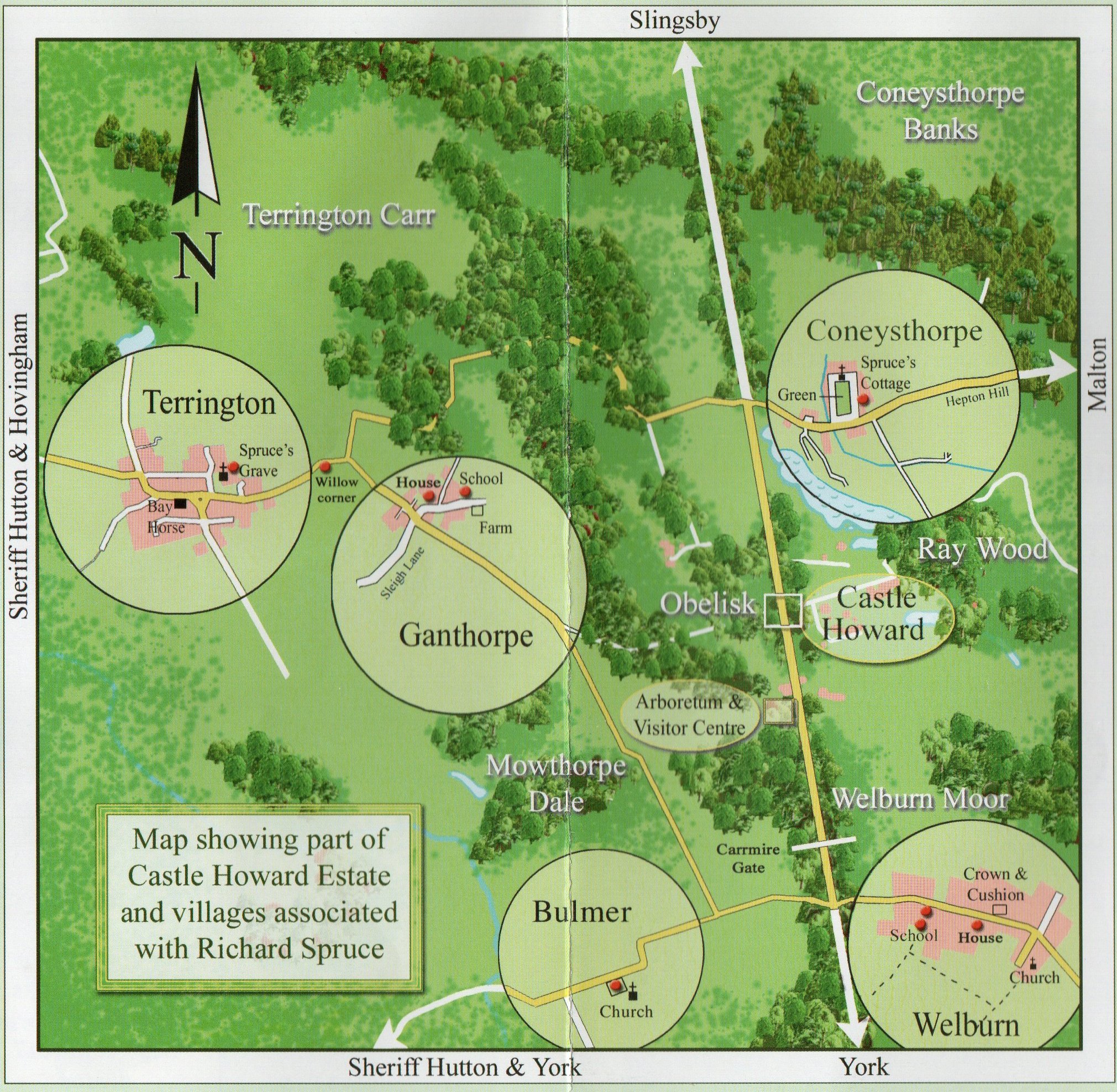

The area which Richard Spruce called home, and where he first gained his love of nature, lies among the Howardian Hills around the villages of Ganthorpe, Welburn, Coneysthorpe and Terrington. Situated about 15 miles north of York, and now designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, it also boasts one of England’s finest stately homes, Castle Howard. Richard Spruce lived in this countryside in the 19th century and in his youth explored the area on foot, noting the plants that grew in the countryside.

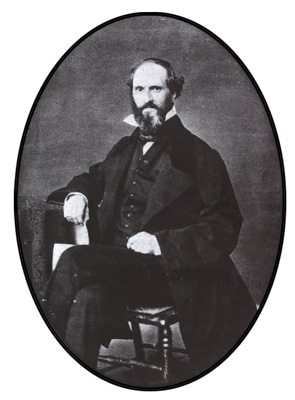

Richard Spruce was one of the greatest Victorian explorers and botanists. He is best known for his journeys along the River Amazon and its tributaries, and for his efforts in procuring seeds and plants of the quinine producing cinchona tree. Apart from the 15 years he spent abroad, most of his life was spent in the villages of Ganthorpe, Welburn and Coneysthorpe on the Castle Howard Estate.

His father was a schoolmaster, and Spruce himself initially became a teacher, but it was not work he enjoyed. As a young man he became an enthusiastic and distinguished amateur botanist with a special interest in mosses and liverworts, and he wished to make a career as a botanist.

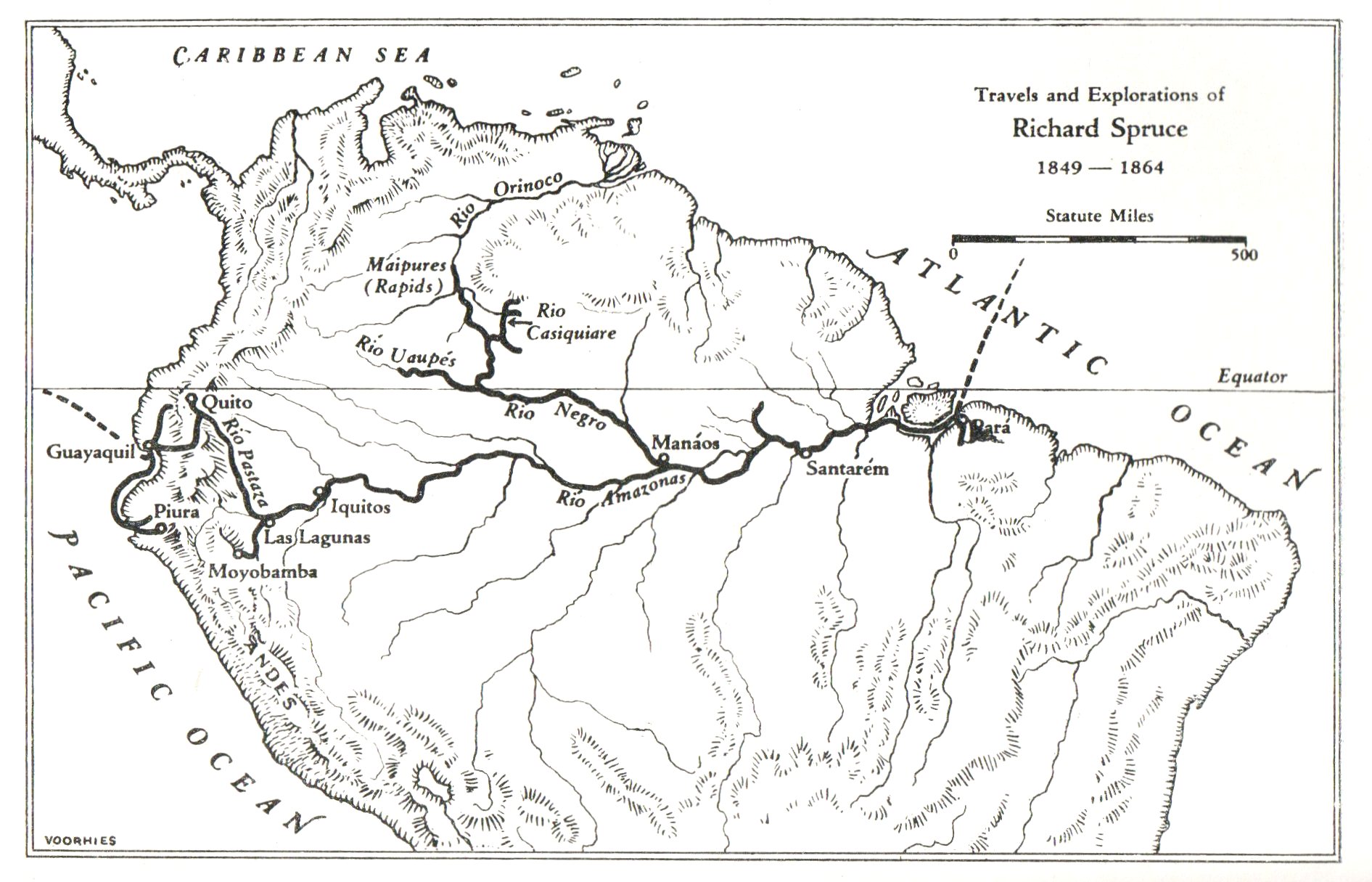

In 1845 he left England to spend a year collecting plants in the Pyrenees. He then undertook a study of tropical plants at Kew and The Natural History Museum which prepared him for an expedition to the Amazon. Encouraged by the director of Kew, Sir William Hooker, he hoped to finance his journey by sending back pressed specimens of flowering plants to sell to plant collectors in England. He sailed to South America in 1849.

It is not easy now to imagine the difficulties and hardships facing a traveller in what was then largely uncharted territory in dense forest, where the only means of access was by river. His health has never been robust, but he coped with fever, shortages of food, dangerous river torrents, immense heat, and at times continual rain. Additional perils abounded in the form of snakes, vampire bats, poisonous insects, as well as treacherous natives and unrest in the countries through which he travelled. His health eventually broke down, and all his savings were lost when a South American bank failed. Nevertheless, this courageous Yorkshireman, by sheer strength of character, overcame all these difficulties.

He navigated the Amazon and its tributaries, mapping previously unknown areas and succeeding in the most adverse conditions to preserve specimens of more than 7000 species of plants, many new to science, to send back to England. Much more than this, his interests extended to all aspects of the countries he visited: the geology, geography, wildlife, and customs, dialects and life of the people. He made meticulous records, illustrating them with his drawings. A tall, dark man with a lively sense of humour that never deserted him, his letters and journals are full of fascinating, and ofter amusing, detail.

Perhaps Spruce’s most lasting achievement was his work in the Andes on the slopes of Mount Chimborazo. Here he gathered thousands of seeds and plants of the quinine-producing cinchona tree (Peruvian Bark) which were sent back to be grown in India for the use of the Empire, thus providing a ready source of this vital anti-malarial drug.

He came back to spend the last years of his life in the Yorkshire countryside. When his health allowed, he wrote up his South American notes and worked on his favourite mosses and liverworts. He was visited by, and corresponded with, notable botanists from all over the world. His efforts in South America were rewarded by a pension of £50 from the Government, secured only through the influence of the Howard family of Castle Howard, and £50 from the India Office.

A much respected figure in the scientific world, he was also honoured for his achievements by the award of a doctorate from the University of Dresden. However, Richard Spruce, eminent botanist, scientist and explorer is relatively unknown now, even in his own area of Yorkshire.

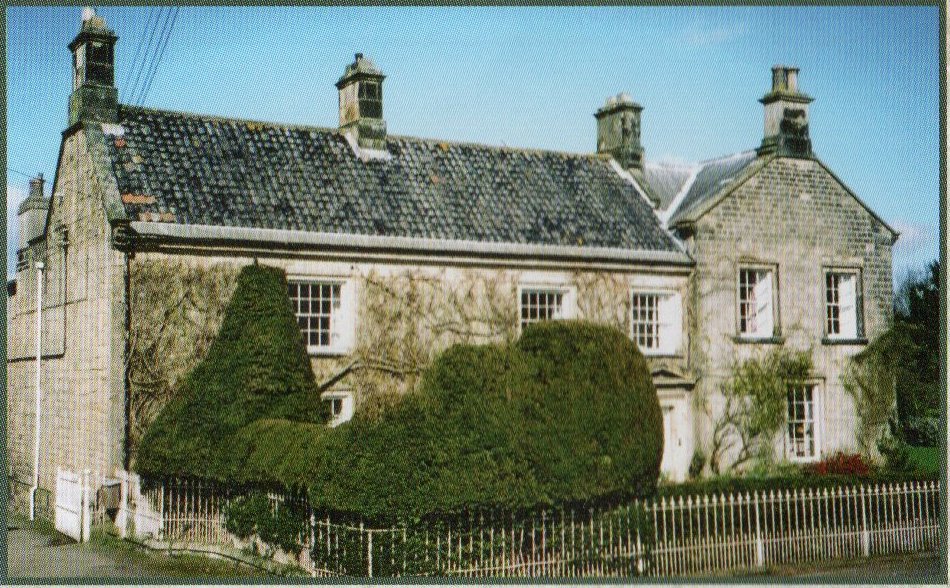

In the year 1817 Richard and Ann Spruce moved to Ganthorpe, where their son, Richard, was born in September. By 1826 the family were apparently living in the 18th century Ganthorpe Hall. Richard attended his father’s school in Ganthorpe and later became a teacher himself at the Collegiate School in York. Richard’s two sisters died young and his mother Ann died in 1829. His father soon remarried and the first four of Richard’s eight half-sisters were born here.

The small hamlet of Ganthorpe has hardly changed, its farms and stone-built cottages presenting an attractive picture of rural England. A walk to the end of the village gives a view of the countryside towards Terrington Carr where Richard first became interested in botany. Mowthorpe Dale nearby was the favourite area where he search for plants.

The grounds of John Vanbrugh’s masterpiece, Castle Howard, were well-known to Richard. One part in particular, Ray Wood, was an area where he gathered mosses. The Earl of Carlisle was a patron of Richard, who sent him Indian artefacts from South America.

Richard Spruce’s father, a schoolmaster also called Richard, lived in Bulmer from about 1806. In 1816 he married Ann Etty at Lund on the Yorkshire Wolds. Bulmer is an attractive Castle Howard Estate village with an interesting church. In the churchyard are interesting memorials to employees of the Earls of Carlisle.

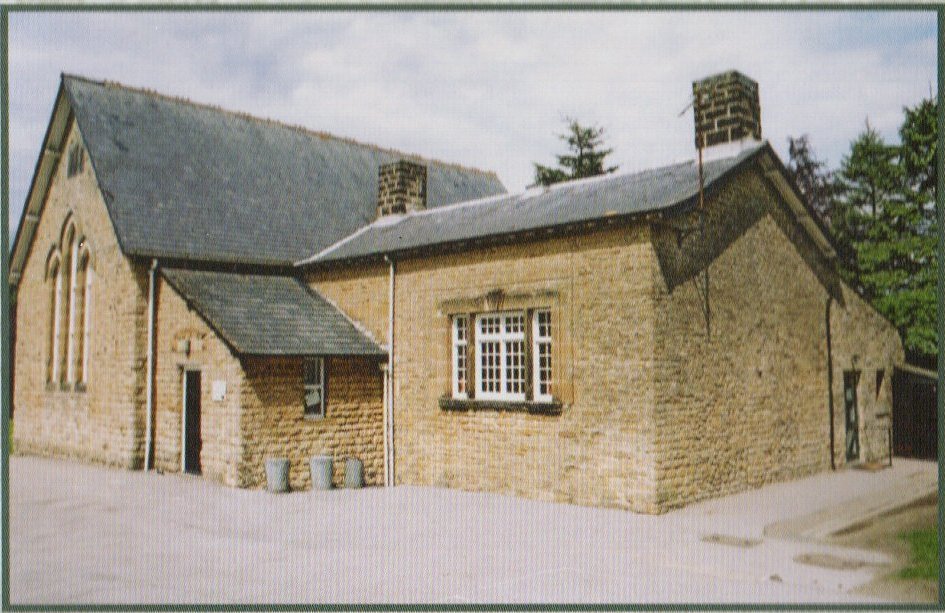

In 1841 the Spruce family moved to Welburn, where Richard’s father was appointed schoolmaster at the newly opened boys’ school, financed by the Earl of Carlisle. They lived in a house near the former Methodist Chapel. Here three of his small half-sisters died of scarlet fever in 1845. The school is along a footpath behind the village street and here Richard occasionally deputised for his father. The older rectangular school building is the one which he would have known.

A footpath leads up the hill behind the school, and from the carriage road at the top is an extensive view of the Castle Howard Estate and the countryside so familiar to Richard. He describes this as “one of the finest views in England”. The walk, on the way back down, passes the attractive Victorian church of St John the Evangelist. Richard returned to Welburn in 1867. At Chapel Garth, a fine 18th century house opposite the ‘Crown and Cushion’ lived his friend John Teasdale, to whom many of his descriptive letters from the Amazon were addressed. Richard, in poor health and with little money, took lodgings in the adjoining cottage (Pitcairn). Here between 1867 and 1876, he lived a very retired life, working on his dried plant specimens, doing much of his important writing and received visits from other notable botanists. In Welburn and later at Coneysthorpe, he recorded many interesting details about village life in letters to friends.

In 1876 Richard moved into a Castle Howard Estate cottage overlooking the village green at Coneysthorpe. It was smaller and quieter than Welburn, and most of his neighbours were farm labourers. Now an invalid and rarely able to go out, he relied for many things on an old friend, Matthew Slater of Malton. Although housebound, he retained his interest in botany and maintained a correspondence with distinguished botanists worldwide. He died there in December 1893 from the effects of influenza.

The plaque to him, which was unveiled in 1971, was paid for by the donations of admirers from twelve countries. A footpath from the north end of the village leads to Coneysthorpe Banks, another area where he sought interesting plants. The elegant small church on the green has recently been restored. There is a fine view of Castle Howard from the village green.

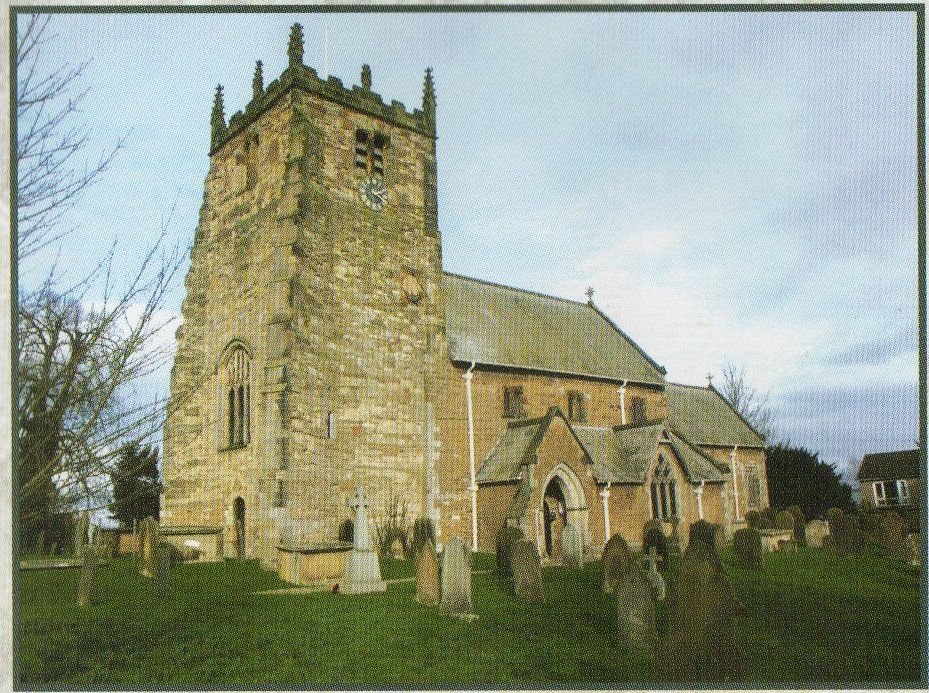

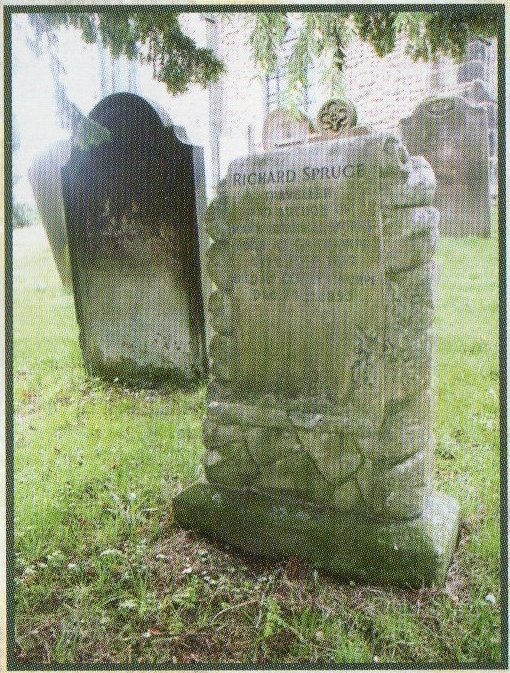

The church of All Saints, where Richard Spruce was baptised in 1817, is an ancient building, tracing its origins back to about 1100AD. The churchyard here is his final resting place, next to the grave of his parents, a marble headstone marking his place of burial.

©Terrington Arts

This page last updated: 21st December 2021