The text below is reproduced, with kind permission of the author and of Terrington Arts, from the booklet published in 1998 by Terrington Arts as part of the Tiefrung project. The project was supported by the National Lottery through the Arts Council of England, and received financial support from Ryedale District Council and many private sponsors in the village.

The booklet shamelessly builds on the work of others, particularly the 1960s Workers' Education Association local history group and Mary Dymond's subsequent scholarly study, 'Terrington - A History of the Parish' (1964). Other collaborators, now in Heaven, were the Victorian antiquarians of Terrington, John Wright (father and son) and the then Rector, Samuel Wimbush.

The author would like particularly to thank the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, York and the family of Samuel and James Wimbush for the access they have given to source material and their help and courtesy in doing so. Thanks also to our supporters who so generously lent pictures, checked copy and gave technical advice, and especially John Goodwill, Lynn Haywood, Gerard Naughton and Penny Sissons for the use of illustrations.

Most importantly, our thanks are due to the many villagers, past and present, and too numerous to list, who have encouraged the project and given us many of the facts and stories which follow.

Terrington Arts hope that this booklet will be not an end but a beginning.

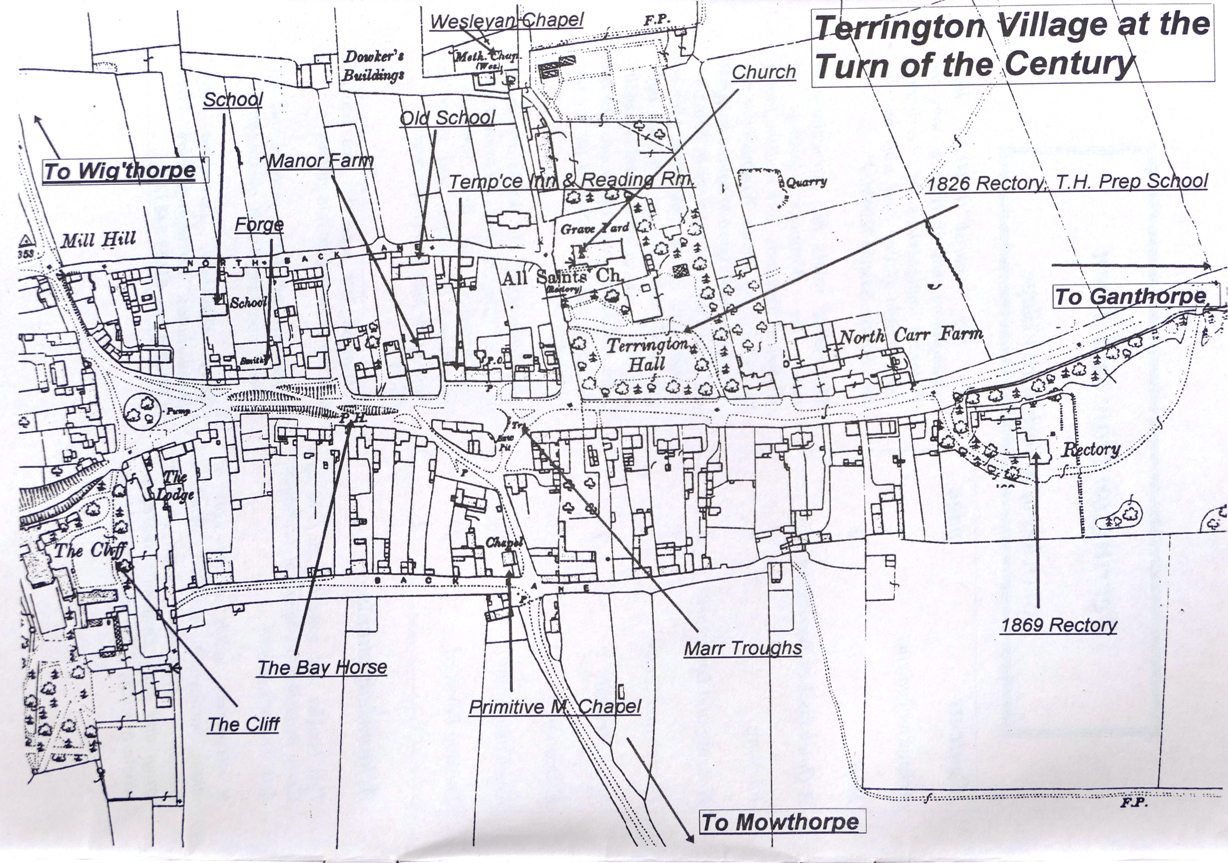

For the visitor, the focal point of Terrington Parish is the Church of All Saints, perched a little above the village street. It looks along the Howardian ridge eastwards towards Castle Howard and Malton, west along the old ridge road towards Easingwold, north to the Vale of Pickering and south, beyond Sheriff Hutton, to York. A mile or two distant are the three Thorpes, which started as Anglo Saxon settlements looking towards Terrington village. Ganthorpe, now a hamlet, was once the centre of a bigger farming community. Mowthorpe has been a backwater, even in this parish, for four hundred years. And Wiganthorpe, once a great Estate, pulling the community toward it in the way that Castle Howard still does in the other direction, now has just a remnant of the old Hall, a farm and a few houses.

The Church has been here far longer than any part of the village you can see. It has some Saxon remnants, and its site was probably a place of worship even earlier. The name 'Terrington' is itself Saxon. Perhaps as the Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names thinks, it is from Tiefrung, 'a picture', hinting at an older history of a Roman villa and mosaic floors. Some have seen its origin in the Anglo-Saxon name for witchcraft. Or maybe it was prosaically named after a Saxon bigwig called Terry?

Today the parish is a pretty spot, but still the right side of chocolate-box perfection. Little, save the church, is much older than Victoria. It is probably home to more commuters than farmers. But its character is still shaped by its rural past.

History has its place in Terrington, but nothing big ever happened here. The interest is in the detail, and that is what these sketches are about.

As you drive through the village, you may see Eric Foster's cows plodding to the milking parlour at Manor Farm in the middle of the village. The village farmhouse was once a common feature and there were at least three others in Terrington's main street. But today, this is one of the last in North Yorkshire.

In 1851, the village population was over 650 and it had about 20 farms of around 100 acres, some owned, but most tenanted from the Estates of Castle Howard, Wiganthorpe or the Church. Each employed five or six breadwinners one way or another, to say nothing of the village tradesmen and craftsmen supporting them. But even by 1912, the population was down to about 450, with many unlet houses and enough young men emigrating to prompt a map in the church porch, 'Terrington Beyond the Seas', showing where they had settled.

Today, thanks to mechanisation, you can walk the fields all day and scarcely see a soul. But the parish population remains at the Edwardian level, thanks to a modern influx of white-collar self-employment, commuting and retirement, and is vigorous enough to support a thriving school, a shop, a pub and a church.

The Enclosure Acts of the 1770s, implemented here in 1779, were designed to modernise and clarify land ownership which had been a feudal jumble of rights and responsibilities holding up the agricultural revolution. When George Hicks leased 3 acres of land from Lord Downe in 1722, part of the rent was 'one fat capon on 20 December' - as far as can be judged, simply because this had been part of the standard deal on that piece of land for hundreds of years. You can imagine George grumbling 'This is 1722, you know, not 1322'.

Until then, Terrington had the usual system of open-field farming, including a few large fields divided into strips as allotments for the villagers, and with few of the hedges, fields and farmsteads which form the shape of the countryside today. No doubt, formal and consolidated land ownership brought economic efficiency, but mostly to the newly confirmed owners. Of 1800 acres enclosed, 1200 went to the Earl of Carlisle at Castle Howard and over 350 to the Church. The rest went 18 ways. There were perhaps 200 families in the parish, so, for most people the benefits were not obvious.

Many of today's farming families have been here for centuries, give or take a little marrying in. But there is a paradox. While agriculture remains the vital local industry, it is no longer the dominant employer it was in 1851 when about half the employed population were in farming (and half the rest, incidentally, were servants). Peter Goodwill of Howthorpe Farm summarises it. 'My father farmed 300 acres and employed 13 men, I farm 1000 acres and employ two'.

But the old field names still resonate in Lord Morpeth's Plantation, Bawdy Hill, Lame Hill, Spittle Field, Bean Syke, Cumhag Wood, Little Barlash. And you can still just about see the remains of the old pound for stray animals near the top of New Road.

Many villagers would keep a pig in an outhouse (now often a smart utility room) or a cow on the Moor, which was managed by the Terrington Town Pasture Cow Club. Membership was compulsory and included some compensation for the catastrophe of losing a beast (remember Jack's mum of Beanstalk fame?). Pasture discipline was nothing new. In 1175 one Daniel of Terrington was fined for letting his cattle stray.

In 1663, William Campleman's two horses vanished. He got into trouble with the Church for going to a fortune-teller, one Walter Johnson of Rillington, for help in finding them.

Farmers' accounts of poor business are ageless. In 1885 the Rev. Samuel Wimbush talked to Mr Kitching, a fellow farmer, and said in his diary 'Calculated with him the cost of producing & delivering an acre of barley. Found it to be £5.9.0. with value today to be £5.12.6. Profit, 3/6d and straw.'

Terrington is a reminder that many apparently 'Olde Englishe' villages were actually nineteenth century developments, made possible by the Enclosures and the agricultural, industrial and transport revolutions. There are few buildings in Terrington which show any external parts from before the Enclosures. Any old structures still standing have been embraced by more recent building work. Most Terrington people's homes before 1800 were probably pretty basic.

A hundred years ago, the Big Houses in the Parish amounted to the Hall (converted from the old Rectory, dating from 1826, and now Terrington Hall Preparatory School); the Rectory (built in 1870 and now Terrington House); the Cliff (also 1870, and now much decayed), together with its neighbouring Lodge; Wiganthorpe Hall (1780s and now mostly demolished), and Ganthorpe Hall (then the Castle Howard agent's home, now privately occupied).

Most other houses were built as estate cottages for labourers (whom the gentry referred to as, say, 'Rhodes'); but there are a few larger but unluxurious properties for tenant farmers and people with skills, such as the smith or the schoolmaster (prefixed by their betters as, say, 'Mr' Shackleton or by their occupation, say, 'Gamekeeper' Hill.) There also remain as today's outhouses one or two bothies, which were basic housing for casual labourers working temporarily in the area.

Mains water arrived only in the 1930s. Until then, you got your water from pumps, some of which remain along the village street - or by arrangement from neighbours' supplies. Mains electricity dates from 1930 and mains drainage from the 1960s.

At the head of the village street stands The Plump, a walled mound containing ancient trees. Its earth probably came from the excavation of New Road or Wiganthorpe Lake, half a mile away, in the early 19th century at the time Castle Howard estate developed the top of the village.

Outside the village, there are old quarry workings, mainly the Jurassic limestone from which most of the village was built. Stone from Mowthorpe was probably used to build Sheriff Hutton Castle 900 years ago, and the Church quarry on the Dalby road provided the stone to build the present village school in 1890.

On the Ganthorpe road, you pass an impressive row of oaks. These were planted for Castle Howard estate, probably by James Elliot, its woodman in May 1859. In recent years the Parish Council has encouraged the tree-planting tradition as shown by the promising rows of trees along other roads approaching the village.

Any student of English village life is drawn to the Church, since for centuries it represented authority and kept most of the records. 'Ye Parish Church of All Hallows, Tyverington' as early records call it is no exception. Dating in part from before William the Conqueror, much of it is 12th or 13th century, but heavily modernised in the 1860s. A good description of its structure and features is available at the church. Don't miss the Anglo-Saxon window in the South aisle, topped with a recycled gravestone, probably about 1200 years old.

Until the 1930s, the church was well endowed through property ownership and the tax of tithes on the parish and the Rector managed the Church farms and reaped the benefit. Patronage of benefices could be bought and sold, and Samuel Wimbush, the Rector of the time reported in his diary in 1885 that he believed the Living of nearby Dalby had been sold for £1225. In the last century this usually meant that the Rector was as much a gentleman farmer and estate manager, as he was a priest.

By the 1950s, the days of grandeur were over. The then Rector gave up the struggle of tending a large mansion on a small income to move to another parish. Within a few years the present modern Rectory was built in its grounds and the Rectory passed into private hands as Terrington House.

But before then, the Living had not always been easy.

In 1239, for example, a brawl in the church between the households of political rivals led to the death of one William of Lydeyate and the imprisonment of Stephen, priest, of Terrington for his part in it. A hundred years later, in 1349, Roger Basset, the rector died. Nothing unusual, until you see a turnover that year of over half the clergy in the neighbourhood. It was the year of the Black Death which wiped out up to a third of England's population and it is unlikely that Terrington was spared.

Apart from the Black Death, another plague for Rectors was the Visitation, a regular formal enquiry by the church hierarchy on the spiritual, moral and organisational state of the Parish. It was frequently fuelled by complaints from the congregation about their neighbours, the Rector and parish officers. So the Visitation records over the Tudor and Stuart reign tell us how those turbulent times for religion affected the Rector and his flock in uneventful Terrington.

They suggest that the Rector of those times found no peace, with Puritan tendencies in one direction, and Catholic recusants in the other making his life a misery.

A zealous Puritan faction in Terrington was probably behind the demands at Visitations for quarterly sermons in Elizabeth's time and the new translation of the Bible in James I's. By 1633 there were complaints about 'Edward Hindsley, Rector of Terrington, for not reading prayers upon the Eve of Sundays and Holydays save only at the feasts of Easter and Whitsuntide and Christmas. Neither does he also wear a hood in reading divine service.' Hindsley's clerk, John Brian, a layman, was also in trouble for the more Dissenting tendencies of teaching in church and reading Divine Service in the absence of the Rector.

Hindsley's successor, Samuel Pawson, was flexible enough to be appointed in 1658, during the Commonwealth, under Lord Protector Richard Cromwell, no friend of the Established Church; and yet to be confirmed and legitimised in 1661 after the Monarchy returned. In compiling the official list of Rectors a hundred years ago, the Rev. Samuel Wimbush, who knew the facts but was clearly a Royalist, chose to record the later date as the legitimate one.

After the Restoration, dissenting from the Established Church, even as a Protestant, became politically incorrect. Thus there was a 1663 report 'Michael Richotson for not coming to his parish church, for keeping his child unbaptised, for burying his wife & a child in his Garden & for keeping private Conventicles (Dissenters meetings) in his house'.

In Tudor times, the North of England did not rush to embrace the Reformation. Many families, led by the gentry, remained obstinately faithful to the old Catholic religion, despite the political pressure to conform with the newly established Church of England and the ever-growing local challenge of the Puritans.

For some time after the Reformation, there was probably still a chantry chapel (as Catholic a symbol as a monastery) at Ganthorpe dedicated to St Mary Magdalen. As late as 1540, William Jackson left money to its priest to pray for his soul, though within the next decade the chapel and its like were dissolved and, as with the monasteries, their property was privatised to Protestant secular ownership. At about the same time, the Stapleton chapel at Terrington Church vanished.

A reminder of those troubled times was the discovery in 1876 of the 15th century Sanctus bell, buried 7 feet below Terrington church tower, probably to protect it from Puritan fury.

In the hundred years or so from Elizabeth I to Charles II, members of the Metham family were the most regular subjects of complaint for 'Popish recusancy'. Unfortunately for the Rector, the Methams were also squires of Wiganthorpe and therefore his most important parishioners, even for some time sharing patronage rights to appoint him. So, it is unlikely that he was behind the 1633 Visitation complaint against Jordan Metham for 'sitting in the Church with his hat on his head during the reading of the first and second lessons. And for not receiving Communion for these seven years last past and more'.

One of the Methams was a Patron involved in a dispute lasting for three years from 1608 to 1611. A new rector, Daniel Lindley, was appointed by the Patron (a Metham). He resigned and was replaced following the arrival of another Patron. He was then evicted but was reinstated after civil action in the courts. Religious rivalries or just a personal vendetta? But Lindley chose to turn a blind eye to the Metham's religious loyalties and in 1612 reported to his superiors that there were no recusants in his parish.

More recently, between the Wars, Mrs Rosalind Toynbee converted a cottage in Ganthorpe into a Catholic chapel in memory of her son, Anthony. The parish's small Catholic community used it until a few years ago, but it has now reverted to private occupation.

It was 1817 before the parish finally got an alternative place of worship in the form of the Wesleyan chapel down the lane behind the church and in use until recent years. Even then, it was with the Established Church's say-so, even if only as a legal technicality. 'This is to certify ..... that a certain newly erected building or chapel situate in Terrington in the County and Diocese of York for which Robert Sporton of New Malton is trustee was this day registered in the Consistory Court of his Grace the Lord Archbishop of York as a place for Public Worship of Almighty God for Protestant Dissenters. Witness my hand this 22nd day of May in the year of Our Lord 1817. Josh Dibble Jnr Deputy Registrar'.

Squire Edward Brooke was a West Riding Wesleyan preacher of renown, and some of his descendants now live in the village. In July 1826, he visited Terrington. 'The Memoir of Edward Brooke' recalls 'It was a hot summer's afternoon when the squire preached at Terrington. The little chapel was crowded with farmers and farm labourers. Oppressed by the stifling atmosphere, he threw off his coat saying "You people strip to gather the earthly harvest, and why should I not strip to gather the heavenly harvest?" In his shirt sleeves, on he went, enjoying wonderful physical relief, whilst the congregation was too impressed by his awful earnestness to be at all shocked by the unusual spectacle.' In the evening his friend, Mortimer, preached. After a woman in the congregation cried aloud for mercy as a perishing sinner, 'the embarrassed preacher exclaimed "This woman's praying is better than my preaching ..." . A great number were converted.'

By the 1850s there was little difference between the number of the All Saints communicants and the combined strength of the Wesleyans and the Primitive Methodists.

The latter had built their new chapel in 1838 at the bottom of the village but in 1867 they sold it for £130 to the Church to be part of the 'new' Rectory site. They invested the proceeds in a new Chapel in Mowthorpe Lane, which later became the Methodist chapel room and later still, the Band Room before becoming a holiday cottage. When the original 1817 Wesleyan chapel closed a few years ago it became the music room of the Preparatory School.

The Chapels were run mainly by laymen. The Church for many years tried not to notice the existence of an 'opposition'. In 1888 after 23 years as Rector, Wimbush records 'Mr Swann introduced me to two Wesleyan ministers'. This was the first time his diary noted the existence of Wesleyans, though their chapel was not a hundred yards from his Church.

Three pubs in a village of Terrington's size tell their own story of the Victorian drink problem on a scale comparable to today's concern about drugs. An anti-drink Abstention movement arose, including the Methodists and the newly formed Salvation Army, together with the American hymnists, Moody and Sankey, who made sure that the Devil did not have the best tunes.

In May 1875 the Rector, Samuel Wimbush, went to one of Moody & Sankey's concerts at the Opera House in London, not once but twice. Within a few months, he chaired a Temperance meeting in the village. By 1882, the Howards had become staunch Abstentionists and (perhaps primed by a rare dinner invitation to the Castle) Wimbush led abstention in the parish, launching a Band of Hope in the village to encourage villagers to pledge total abstention. In one move he had done good, stolen the Methodists' clothes and gained an entrée to Castle Howard.

At his first Band of Hope meeting in 1883, 55 people signed the pledge, and soon afterwards, 55 children at the Sunday School followed suit. He even floated the idea of a 'coffee tavern'. Later that year, there was a huge Temperance demonstration at Castle Howard, where the Howards of the day are said to have emptied their cellar into the lake. But not all signed with the same commitment - in 1884, Henry Blakey returned his Pledge simply in protest at the Rector's refusal to lend the school for a dance.

Later in the same year, however, Wimbush was instrumental in changing the tenancy of the Cross Keys public house (now Hope Cottage, opposite the Village Stores) no doubt with the support of the Howards who owned the site. In his diaries, he writes, with some satisfaction, 'The Cross Keys, now to be the Reading Room and not the Cross Keys'. To be on the safe side, the new tenant was the Rector's trusted gardener and fishing companion, George Coatesworth. Within living memory, the same house was the Temperance Inn (see The Visitor Business, below).

The diocesan Visitations highlighted more human problems. In 1607, pity Roger Young. 'Against Roger Young. He is not sufficient to be the parish clerk, he cannot write & scarce read, he cannot sing at all'. But another entry suggests a village scandal, which may have been behind the accusation. 'Against Alexander Berier, unlawful dealings with Cicilie, wife of Roger Young with whom he was in evil name before'.

And, from 1594, just as a sample of many clucking tongues over many years, 'Against Thomas Barker, Elizabeth Tonge, Margaret Hicke and John Heard, fornicators'.

Most of us have dozed through sermons of greater significance to the preacher than the congregation, so we can sympathise with the guilty men of 1633. 'George Milson, Richard Peckitt and Edward Lyon for sleeping in the Church in Service time'. And even with 'Francis Gooderick for mowing grass upon St Bartholomew's Day last in service times'?

Until the 19th century, the diocese was for practical purposes the local authority, and thus, the approver of licences to work at some trades. This is an example from 1736. 'FACULTY On the 2nd day of April in the year of our Lord aforementioned, a licence is granted to Margaret Hawker of the parish of Terrington ... to exercise and practice the business of midwife in and throughout the whole Diocese of York'.

For centuries, before we all had watches, the church was guardian of the time for the village. As late as 1916, the Hall was asked to clear some trees so that the church clock was visible from the village. As early as 1621, there was a contract with William Wilson, a York clockmaker, to repair the clock when required for a retainer of 5 shillings a year. By 1767 a sundial had replaced it. It is still in place facing South on the tower and gives an accurate reading. The current clock dates from 1876, but remains accurate enough to set your digital watch by.

The Church has given the Parish continuity over the centuries. Leonard Thompson, John Cayley, Charles Hall, Samuel Wimbush, James Wimbush - in the two hundred years from 1734 to 1933, Terrington had just these five as Rector, an average of about 40 years each. The last two were father and son.

This continuity may not be quite what it seems. Thompson and Cayley may have left much of their spiritual duty to their curates, and there was no requirement on parsons until the 1820s actually to reside in their parish.

Back in 1743, there were 100 communicants at Easter in this parish of about 700 souls. In secular 1998, with little peer or squire pressure, there were about 50 Easter communicants from a population of about 450, a fall from about 14% to 11%. A hundred years ago, Samuel Wimbush had only one parish to run, compared to the present incumbent's five and he ran three or four services a week. But even with a captive audience from his own large household and those of sympathetic gentry, his monthly count of communicants rarely went much above twenty. So it seems that the golden days of the country parish church were not quite as shining as we think.

The Howards bought the Terrington part of their estates from Lord Downe in 1752 and still own much of it.

They brought (and still bring) a generally benevolent air of power and prestige to the neighbourhood. You brushed against greatness to have as your landlord or neighbour not just an Earl, but a family who entertained the Queen (1850) and even Mr Gladstone himself (1876). Incidentally, Gladstone was 'drawn by hand from the Inn to the Castle'. (Both may have approached the Castle from the Station through Exclamation Gate, so called from visitors' reaction there to the sudden vista of the castle.) Small wonder that for many villagers, until recent times, the only time they wore their best suit was when they went to the Castle to pay their annual rent.

One legend from nearly four hundred years ago speaks of them and their neighbouring squires in the parish. Samuel Wimbush in his diary reported a story of Stuart times from a local antiquarian. 'Nov 4 1885. Mr. Wright told me that once Sir Henry Slingsby, Sir William Strickland of Coneysthorpe, Sir John Dawnay (afterwards created Lord Downe) & Charles Howard Esq., afterwards created Earl of Carlisle by (I think) Charles I, stood at the east end of what is now Lord Morpeth's Plantation & drank each others health, passing the cup to each other without moving out of their several estates'.

For most of the time since the Conqueror, the Lords of Wiganthorpe Manor have been close to the village, though their names have changed through the generations. In the 13th century, the splendidly named Anketin Malory was lord of the Wiganthorpe manor.

Then came the Stapletons. As Patron of Terrington Church, in 1311, Miles Stapleton appointed a rector named Wodehouse. Fate dealt his successor at Wiganthorpe in the 1930s a butler called Jeeves! Perhaps Miles descendant, Brian, is to be thanked for this happy coincidence since, later in the 14th century, he endowed a chantry attached to Terrington church and funds for a priest to say mass for him and his family.

In Elizabeth I's time came the Methams. By then, there was a substantial house, described in 1595 in Francis Metham's will as including a hall, two parlours, glass in all windows, doors with locks and keys, a brewhouse, stables for oxen and horses and railings round the house. As Catholic recusants, their relations with the Protestant Establishment were at best strained, but they lasted as squires till 1653 when George Metham sold the estate to John Geldart whose family succeeded him through various name changes by marriage for about 100 years.

Then came the Garforths, a merchant family from York, led by William, who in about 1780 commissioned John Carr, the distinguished architect of Georgian York, to build a new Hall onto the Jacobean one. His nephew, another William and a naval man, but best known as a bloodstock breeder, succeeded him. Indeed, if you look up Wiganthorpe on the Internet, the only references today are to breeding stables in Ireland. The nephew also set up sawmills, perhaps by what is now Sawmill Cottage by Wiganthorpe Lake.

The aristocratic Hon. William Henry Wentworth Fitzwilliam, second son of the 6th Earl Fitzwilliam, bought the Estate in 1890, carried out extensive renovations to the Hall and moved in with his wife Lady Mary Grace Louisa, daughter of John Butler, 2nd Marquess of Ormonde. He remained there until his death in 1920 when the estate was purchased by Lord Holden, a West Riding millowner, who made up for any lack of blue blood by employing one Mr Jeeves as his butler.

By 1937 the estate was sold again and was on the slippery slope to division and demolition, finally achieved in 1953. Today, only the site of the Jacobean hall remains, heavily Victorianised; and the plough has reclaimed even the carriage drive through to Terrington.

A local historian earlier this century, writing of the eighteenth century houses, may have been thinking of Wiganthorpe Hall when writing of the building mania, 'hundreds of pretentious grand houses now a burden on their owners'.

Although the Worsleys are usually associated with Hovingham, the family has had a long connection with Terrington. Part of the family bought the old Rectory in the 1860s and made it the Hall (today the Preparatory School). Others, in 1870, built The Cliff, the once-imposing residence at the top of the village. They owned land around the village. They were committed supporters of the Church, and provided the site of the present Church of England school. So at different times they owned the sites of both schools now in the village.

In the churchyard, at the East End of the church, is the grave of Richard Spruce (1817 to 1893). The son of the Ganthorpe schoolmaster, Spruce was a self-taught botanist who became a major plant-hunter of Victorian times, bringing back from the Amazon and the Andes vast quantities of specimens for British scientific research, as well as rubber and quinine plants for propagation around the Empire.

Forgotten in England, he is fondly remembered in the USA through the Spruce Society who visited Terrington at his centenary. Could this be because he was the first European to try the Andean hallucinogenic drugs related to modern LSD?

Another distinguished scholar from Ganthorpe (it must be something in the water) was the historian, Arnold Toynbee OM (1886 -1975), whose family still live at Ganthorpe Hall.

Before the Toynbees, the Hall had long been the residence of Castle Howard's agent.

For about thirty years, Sir Alfred Lascelles, former Chief Justice in Ceylon, lived with his family at Cliff House. Sadly, his only son's name can be read on the War Memorial and with him there died the family connection to Terrington. But there had been Lascelles in the Parish long before him. In Elizabethan times they owned Howthorpe, then considered part of Ganthorpe, and the neighbouring property of Airyholme, looking towards Hovingham. They were then called Jackson, but were granted the Lascelles arms in 1584.

They were mostly Catholic. In fact, in Charles II's time, a relative, Catherine Lascelles, came from Germany to found a Catholic convent and spent several years imprisoned in York Castle for her trouble. In contrast, Col. Francis Lascelles, a descendant of the Ganthorpe Lascelles, was on the Roundhead side in the Civil War. He was one of the judges in the trial of Charles I, but thoughtfully was absent sick on the day when sentence was passed.

Samuel Wimbush and his son James were Rectors of Terrington for 68 years from 1865 to 1933. Samuel, from a prosperous Finchley family and an Oxford man, immediately took against the old Rectory (now Terrington Hall Preparatory School, next door to the church). It had been built by his predecessor only 40 years earlier, and was once said to be the largest rectory in Yorkshire. In turn it had replaced one recorded in 1760 as including 'one parsonage house, one dove house, one orchard, one garden, one large court before the house, one little garden and a little house adjoining beside the gate which goes into the town, now repaired and converted to a school-house'.

Wimbush set to building a more modest mansion, now Terrington House at the foot of the village, spending several years while it was being built camped out in the neighbouring Rectory Farm. Until recently, the rectory included a porthole-shaped window, which was said sentimentally to celebrate the ship on which he and his bride passed part of their honeymoon.

When not tending his flock and raising his family of nine children, he managed the Church's three farms or slipped off to go trout fishing in the Rye or the Costa.

He modernised the church (1869), and saw that the village school was built as a Church of England institution (1890). He was secretary of the pioneering Reformatory near Castle Howard, founded by the Howard family. His diaries give a good portrait of family life in a Victorian rectory and much of our knowledge of Terrington comes from his antiquarian studies. By 1879 one of his sons rode his new-fangled bicycle to Hull and had taken up lawn tennis, just invented, at Wiganthorpe Hall.

Just outside the church porch, you will see the grave of George Coatesworth 'for 35 years the faithful servant and friend of the Revd Samuel Wimbush. He died on the 23rd of January 1904 aged 67 years'. Coatesworth was the rectory gardener and died just before the churchyard closed for burials. It is nice to think that Samuel arranged for his old servant, friend and fishing companion to occupy this prime site among the local worthies while awaiting the Last Trump.

In 1908, Samuel died and was succeeded by his son, James, formerly of Sunderland, Bulawayo and Bath - an eclectic bag of ministries to come home with. The church was in the blood, for one of James' sons, Richard, became a bishop.

In 1933 James Wimbush was about to retire as Rector and leave the village where he was born. To preserve his memories, he photographed his parishioners outside their homes or in their teams and thus preserved a now bygone world. For some, he added a few affectionate lines of verse. The first verse below is about the families of village tradesmen, the second about Terrington's football team.

'Of Masons & Joiners we have a good share,

There's Goodwills & Craven & Goodricks & more

They're gardeners too; their apples for size,

At the noted York Gala would take a first prize'.

'We'd a football team once, 'twas a most gallant crew

Father Green was the boss and had plenty to do

Why, we once won the cup, 'twas a glorious day

But alas for those glories, they've now passed away'.

You can pick any one of half a dozen family names in the village and trace their ancestors back for four hundred years through the churchyard and the registers. But among the living and the dead you will not escape the name Goodwill, which is to Terrington what Jones is to a Welsh village. Some Goodwills are related, some are not. In his diary, Samuel Wimbush kept them distinct in the Welsh way - shoemaker Goodwill, joiner Goodwill, tailor Goodwill, Wiganthorpe Goodwill and so on. They have been parish clerks, teachers, churchwardens, carriers, builders, butchers, farmers, and even private cemetery proprietors.

Oldfield is another local name. This epitaph was recorded by the Victorian antiquarian, John Wright, on a gravestone now long defaced. 'To the Memory of James Oldfield who died in Coneysthorpe, September 20th 1831 at the early age of 32. In testimony of admiration of his skills as a worker in stone and of respect for his character as a man, this stone was raised by George Earl of Carlisle. 1832.'

Not far from the porch, however, you can find the grave of Mary Lister who died in 1879 aged 101 years, the only recorded centenarian in the village. In his diary, Wimbush makes no reference to her remarkable age, just recording 'Buried Mary Lister'. To us, she sounds like ancient history. But there are people still around today who knew Wimbush's son - the son of a man who knew and buried this lady who was born when Mozart was aged 22, Napoleon was aged 10 and the American colonies were still fighting for independence.

The earliest record of a school is in 1705 when the Rev. Elyas Micklethwaite recorded in a note for Diocese records 'the present incumbent has built a school house'. It was replaced in 1833 by the old schoolroom in North Back Lane, now a cottage called Brindle Court.

There was at that time a separate school at Ganthorpe, supported by the Howards. Its master was the father of Richard Spruce the naturalist. The older Richard is described on his gravestone in Terrington churchyard as follows. 'Richard Spruce ... having been, during upwards of 40 years, schoolmaster upon the estates of the Earl of Carlisle, who put up this stone as a memorial of the faithful and conscientious manner in which he discharged the duties of that responsible and honorable office.' Not a bad obituary.

The Howard family had a robust influence on education in Terrington. Looking at the calm and respected Church of England school in the village today, it is hard to imagine the stirrings caused by its building in 1890.

In the 1880s, compulsory education was quite new. An Education Department inspection had condemned the old school as 'dirty, small and inconvenient'. Shackleton, the schoolmaster, was fairly competent, but church management had been weak - rarely had the school managers' meetings been quorate. The Church expected to continue in charge of a new school, but others, led by the Howards, had other ideas. This was not surprising in a village with two Methodist chapels and a history of militant ratepayers refusing to pay the Church School rate.

In 1889, there was a 'lively meeting' of ratepayers, as the press described it, to decide the issue. The Rector defended the Church's stewardship of education, saying that the Church had done a good job at only a modest cost to the ratepayers and denied that those who were not members of the church had been oppressed (in 1990s language, 'had been discriminated against').

Mrs. George Howard responded that the Castle Howard estate would pay £500 toward the cost of a new Board school or non-denominational school; but not towards a Church school 'which belonged to one particular sect'. The advantages of a Board school, she said, were political and (with perhaps more truth than tact) 'somewhat difficult to grasp for a set of electors who had not been in touch with popular representative government'. She went on to stress that people should speak up for their own concerns and have some voice in their management.

William Worsley, speaking in favour of a Church school, magically produced a rabbit from his hat, saying, 'the necessary funds had been provided for the purpose and also a site to erect the building on'. ('Prolonged cheering' followed according to the press.) In fact his family had provided the site. After this appeal to the ratepayers' wallets, their vote was in favour of a Church school, though it could well have gone the other way if everyone had the right to vote.

The Rector's daughter, Mary, said in her diary that 'Mrs Geo. Howard made a very long and eloquent speech' but that Mr Swann (another speaker, a local tenant farmer and Methodist, and a Liberal supporter fallen among Conservatives) 'was hissed off the platform'. The Rector diplomatically limits his entry in his diary: 'Parish meeting about school in evening. Mr & Mrs Howard were there, and both spoke'.

By October 1890, the school, with schoolmaster's house, had been built on the site of 'The Bull', a pub which had closed just a few years before. Once again Progress triumphed over the Demon Drink. And the architect of the new school was none other than one Mr Arthington Worsley.

The row rumbled on even after the school was finished as the Howards fought to get back the old school building (leased from them by the Church) in time to open their own undenominational 'British School' which remained open for another seven years. Eventually, the old school building was sold to the village by the Howard family on generous terms and was declared open by William Worsley as a village hall and reading room in 1926.

But even in a 19th century village there was also basic private education. There was a 'dame school' in the Square, run by an old lady who would teach for 1d a day, no doubt filling in the cracks of the state-supported village education provision which some villagers wished to opt out of.

Given what happened to many big houses, fate was kind to Terrington Hall when it was acquired in 1920 as a private preparatory school. It has been part of the economic and social life of the village ever since. Under its recent headmasters it has developed as a happy and successful place where earlier spartan conditions and eccentricities are long forgotten.

Unlike the pre-war days of an earlier headmaster, who disappeared forever one night with the cook, leaving his wife to run Sports Day on the morrow!

Another long-serving headmaster, Peter Clementson, is remembered by a plaque in the church, presented by his old boys, with the Biblical inscription 'My son, obey thou My law'. Schoolboy humour never grows up.

The upper classes of Terrington were always part of a bigger world. They were educated privately, away from their country community; they had time and money to travel for business or pleasure; and they had contacts throughout the country or even the continent. Samuel Wimbush, for example, in the 1870s, would ride to Barton Hill Station, have a business breakfast at York's new Station Hotel and catch the ten o'clock express to London to be at his father's house in Finchley, London, for tea. The Worsleys of his time would retire to Scarborough for the winter. If the gentry fell ill, then Switzerland or the Mediterranean might beckon.

But for most villagers before the Great War and many after it, Terrington was an enclosed community where you were born, lived, married, raised your family and died. The only way out was to the cities or the colonies and it was usually a one-way journey. (Often, the emigrants lost touch, either through thoughtlessness or illiteracy. A regular task of the Rector was to trace a wandering son for his mother.)

All of this required a self-sufficient community. People still remember butchers, a co-op store, a cobbler, a blacksmith, 'Leaf's, Tailors & Breeches Maker' in what is now the Bay Horse Inn's dining room, a village pig-killer, visiting tradesmen's vans and Terrington's own bus business. Before that it had clubs to bulk-purchase coal and the like. In Victorian times it supported three pubs. Today, although the pub and the village stores remain in good fettle, the petrol pump and the village bobby have gone and the bus service is infrequent.

Health was a constant concern, regardless of status. Many of those in the churchyard died of typhoid or scarlet fever. The nearest doctor was an hour's ride away in Malton, cost money and had a limited range of drugs. Illness did not respect class. Samuel Wimbush's wife played the organ in church on Sunday and was dead of pneumonia by Friday. Major Garforth of Wiganthorpe survived the Indian Mutiny, only to succumb at 41 to tuberculosis.

Serious illness among the villagers had a pattern of inevitability in Wimbush's diaries. 'Visited Beal' would be followed by 'drafted will for Beal' and a few days later 'Beal appears to be sinking' and then 'Beal died last night' followed a few days later by 'Buried Beal. Read Will to his family'.

At a mundane level, Wimbush constantly complains in his diaries of colds, toothache and headaches without so much as an aspirin to help. Today, the village has its own well-equipped surgery.

But Victorian post was fast, and letters were dealt with more promptly than in our computer age. Wimbush could order seeds from Suttons of Reading in the 1870s and have them back in a week. He could write to the War Office enquiring after a soldier who had lost touch with his mother, receive a form to complete two days later, and within another week have confirmation of the boy's address in Malta. He could see his son off from London to Germany on Thursday and get a card in Terrington the next Monday to confirm his arrival.

The first known tourism venture in Terrington was the Spa. In the early 18th century, and like any village with some water and a little enterprise, Terrington had a spa to treat rheumatic ailments on what is now a marshy patch on the corner half a mile along the road from Terrington to Ganthorpe. The Earl of Oxford, staying at Castle Howard for Hambleton Races in 1725 described the Spa as 'an open space dug into the ground, like a grave or sawpit into which those seeking relief immersed themselves'.

The Victorian railway lines were just too far to bring day trippers, but they brought the families and friends of the gentry keen to escape the stress of the city and relax in the fresh air, perhaps with a bit of hunting, shooting, or tennis. Not much changes, and today's villagers regularly (some say all too often) find their guestrooms filled with friends and family coming for a country holiday.

By the 1880s, the Howards organised country holidays around their Estate every summer for poor children from Leeds and Bradford. The Estate lodged them with local families at six shillings a head, and no doubt this early example of a 'cash crop' from visitors was welcomed.

In 1921, the Hope family opened their Temperance Inn, which attracted country holidaymakers from all over the land. One little ditty from in their visitors' book summarises its charm:

'Terrington stands on a hill, O! miles from any station

Say what you may, go where you will, its IT for the vacation

Its greatest charm, the peaceful calm, Where no-one seems to worry

A fortnight flew 'n how, we ne'er knew. To leave it all, we're sorry.'

James Wimbush also had a rhyme in his album about the Inn:-

'At Terrington we have a Temperance Inn,

If you get your meals there, you'll never grow thin.

Mrs. Hope is the landlady, smiling and neat.

You'll find Horace and Stan on the bus drivers seat.'

Horace and Stan, the Hope sons, started a regular bus service to York and Malton (plus private hire outings) which did much to take the village to the outside world, and bring visitors to Terrington. It is much missed.

The Victorian walkers and cyclists of Yorkshire found the village; and Terrington has been on their routes through the century. Today, the walkers still come here for a pleasant stopover on the Ebor Way and Centenary Way, or just as the first good walking area north of York for a day out. Squadrons of cyclists come through, sometimes hundreds on charity rides. It is often a convenient stop for vintage car and motorcycle rallies. But for many, staying in the holiday cottages or enjoying a meal and drink at the Bay Horse, just doing nothing and enjoying the peace is all they ask.

Our first records are Victorian. Every summer at the end of term there was a School Feast, for about 130 children and mainly featuring huge quantities of bread. They might graduate, if churchgoers, to the annual choir outing, perhaps to Whitby or even to Fountains Abbey on ambitious day trips.

The whole village looked forward to Terrington Feast, the Club Feast of the Oddfellows, starting on Low Sunday, a week after Easter. It continued on the Monday with horse racing on Freers Moor (in later years on Vesters Pasture in Mowthorpe until about 1880 when racing stopped); and then with a horse show and cricket match on Tuesday. Sometimes there were also evening concerts. Eventually the Feast moved to the summer and reduced in scale.

Occasionally, the Rector might organise a public tea and dance. At most of them, there was a village band to play. The band played at all the village festivals and survived until the 1960s.

By the 1880s, village concerts were a regular feature of life, usually to raise money for a cause. One might be in aid of the reading room, which normally opened on winter evenings. Another, in 1914, lists in its cast, George Chapman and Frank Fisher, soon also to be listed on the War Memorial.

Terrington has always had plenty of sport. There is still a football team, though the cricket pitch disappeared in 1967. Bowls has featured for generations, on a green with a thirty mile view, and folk dancing flourished in the 1930s.

For the Victorian gentry, hunting and shooting in winter were complemented in summer by a hectic round of picnics and tennis parties and a continued circle of visiting and being visited by friends, neighbours and relatives. The daily energy they all used, ladies, gentlemen and children, to walk and ride for miles around would exhaust today's keep-fit enthusiasts.

The 1870s and 1880s was a small ice age, so skating on the lakes at Castle Howard and Wiganthorpe were regular winter events. In February 1879, there was even a cricket match on the ice at Castle Howard. The last freeze hard enough to allow skating there was in 1964, but even today, when Terrington gets snow, most of York comes to toboggan on the Bank.

Terrington has had a village hall since 1926, without which its community life would be diminished. The first hall was the old school (now Brindle Court) and the second was Cliff House, famous for miles around for its village dances. The third and current hall in Mowthorpe Lane was purpose-built in 1994 and features activities from Aerobics and Arts & Crafts to Women's Institute, Wedding Receptions and a Wine Society.

The old village customs were recorded just in time by a Workers' Education Association group in the 1960s who recorded the memories of older villagers who could recall Victorian times.

Terrington's marriage traditions have mostly gone. One was a race down the village street by the young men for a handkerchief held by the bride and groom. At Dorothy Wimbush's wedding in 1898, the Malton Gazette records that William Lacy won it, but there were only two finishers from five starters. Another custom was to put gunpowder in the indentation on the blacksmith's anvil and explode it with a hammer known as firing the stiddy. Yet another custom, recalled in the 1960s by one Mrs Rodwell remembering her own wedding day, was the bride throwing a plate of cakes over her head to break it. Still surviving today is the tradition of children tying up the church gate during the service and cutting the ties only in exchange for money.

The group also recorded a tradition of burning the effigy of an adulterer outside his door, while villagers sang a song beginning 'Rang-a-dang-dang, Now we ride the stang'. They thought it had last been performed in about 1890. They also reported the duty of the publican to duck strangers in the Marr pond near the present shop - unless they paid their footing (maybe a round of drinks?).

They also record that on old May Day (13 May) villagers made garlands of spring flowers and hung them on their doors. This may have been a Victorian invention, like so many features of Merrie England, but Miss Egerton of the Cliff in Edwardian years gave prizes for the best. On Shrove Tuesday the village boys and their mothers played a ball game with home-made bats and balls, and at eleven o'clock a village boy rang the pancake bell (one of the church bells). The last to do so was said to be Jack Goodrick in about 1890.

Another holiday was Ascension Day, 'Spanish and Water Day', when the children dissolved liquorice ('Spanish') in bottles of water by rolling them down Combe Hill by the cemetery and drinking the result. This reflected the more universal custom of egg rolling at the same place, recalled from his youth by George Goodwill. Finally, there was Guy Fawkes Night, with not only the fireworks familiar today but also burning a tar barrel.

'The times were as good or better according to many of the older inhabitants.' This is not a contemporary quote but one from the Yorkshire Gazette of May 18 1912. So the good old days were always better?

But if the people in this book could come back today, would they agree that Terrington is not the village it was?

'Yes', they would all agree, but most would add 'and all the better for it'. They might be concerned that the ties within the community were looser. They would see the irony that their children may have left for lack of work around the parish while today's youngsters have problems staying because prosperity may put affordable housing beyond their reach.

But they would be glad to see the things they never had - running water, drains, good health, good housing, an easing of the physical grind of earning their living or keeping house, a general standard of living beyond their belief. And they would be delighted at the educational opportunities, which were denied them.

They might be surprised to see the parish not much changed, though much neater. They would be glad to see that there were rules to protect the countryside that they had passed to us. They would be astonished by the productivity of the fields and sad perhaps that there are so few people in them. But, thanks to the mixture of new occupations with old farming, they would see, not some half-empty country heritage park, living on its past, but a full school, well-kept houses, a well-patronised pub, shop and village hall. In short, a thriving community with a future bigger than its past.

©Gerry Bradshaw & Terrington Arts

This page last updated: 21st December 2021